Bread That is Also Wafer

It is always worthwhile to pay attention to writers who write ordinary time well. They are almost always writers who blur the distinctions between sacred and ordinary time, who place a piece of bread in their reader’s hand that is also wafer. Jane Craven is such a writer. Her poetry is awake to what is simultaneously the living and the dead in the world around us—for Craven, the world is charged, it has a hum. I think of the line in Gerard Manley Hopkins’s sonnet “God’s Grandeur,” and how Craven’s work also holds the expectation that the world will “flame out, like shining from shook foil.”

One of my favorite poems in My Bright Last Country, which I find myself returning to, is the poem “When There Were Zombies.” Perhaps because Craven is from Carolina soil and I have now lived in North Carolina for a decade myself, there is a special eeriness to the poem’s southern setting:

By the time we knew

she was in the barn,

on the archetypal farm

found by location scouts

in the middle of Georgia,

the farm with its hills rolling

in all the right places,

with its farmhouse, sufficiently

farmhouse, and white,

what was going to be

done to her

had already been done.

The reader is being told a story—a story with delineations into the poem’s setting, the farm, the kind of Georgia landscape the poem resides in—and the line breaks function as dramatic pauses in the narrator’s story. What had already been done to the “her”? The poem does not share. (How well the silence of poetry reflects the organic gaps in all conversation, in all thoughts and memory.)

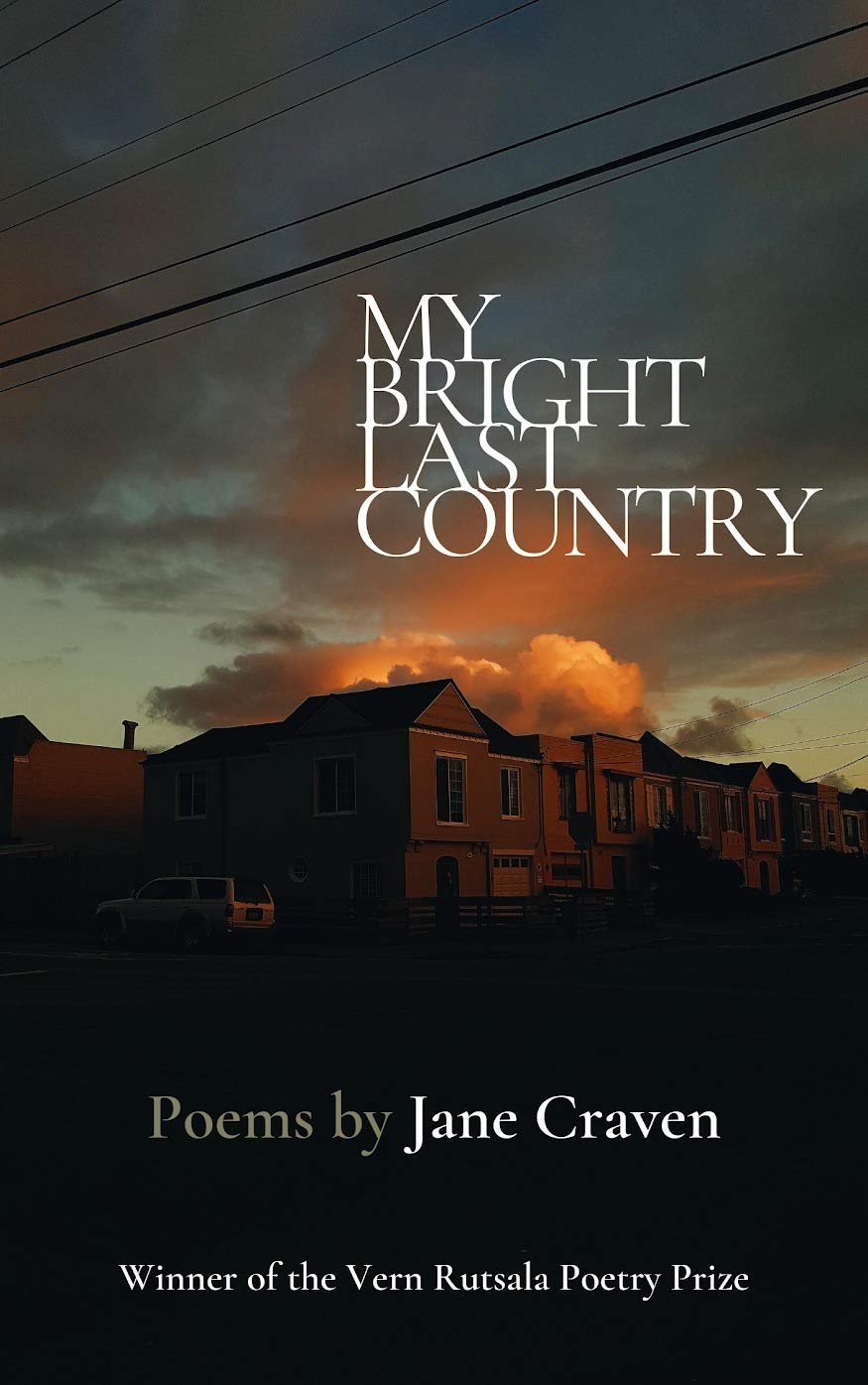

My Bright Last Country by Jane Craven. Cloudbank Books, 2020. 71 pages. $16.

What the narrator witnesses: “Even so, the small clawed hand, / dirty, inching its way around / the finely weathered barn door.” Craven lets the metonymic detail “small clawed hand” draw the entire figure and scene. Without warning, the poem slips into second person:

Your eyes brim at the brittle

girl no longer a girl

as she stands in the farmyard

a ruined shell.

Then, a dramatic turn, though not unexpected if one has read the poems preceding “When There Were Zombies”—poems such as “Meditation in Gold and Indigo,” “The Sketchbooks of Hiroshige,” “Vanitas” (“The goblet is the first thing I notice / in a Dutch still life”), and the poem “My Mother as Aria.” Craven is a poet who works frequently and relationally with other form of arts—visual, musical, and thus it is not entirely a surprise when the former-girl-now-zombie transforms into a classical subject of art: Daphne, pursued by Apollo. The poem describes (in either the internal monologue of the “you” or via an omniscient narrator):

But she is only light and shadow

in the form of a nymph

pursued by a god, her desperate arms

leafing out, not metamorphosis

but perception, something glimpsed,

not changed.

“She” has not altered, but the viewer has—changed by their positionality of viewer and their “perception…something glimpsed,” a kind of metamorphosis. The poem doesn’t tell the viewer how to see the figure by the barn—“she is only light and shadow.” That’s not what poems do: preach. Instead, they ask the reader to attend, to look again. And what we see is something different from what we expected—something more ephemeral, changing. Sometimes it is not closeness we need from a subject, but distance, as the young zombie comes to resemble: “A girl like all the girls made of pixels / you have to be far from to see.”

If you had told me I would fall in love with a tender zombie poem before reading My Last Bright Country, I probably would have laughed. But poetry dares, every day, to do the impossible—to light up a space where before was only shadow. As Dickinson wrote: “I dwell in Possibility -- / A fairer House than Prose.”

To return to Craven’s writerly relationship to art, the poem “A Reconstruction of My Great-Grandfather Who Died of Asthma at Age Fifty,” attends to the speaker’s inheritance of art and labor. The poem includes this epigraph from a 1898 edition of the Railroad Car Journal, published by the Locomotive Painters Association: “The ceiling is covered with canvas, painted blue,…the central portion is filled out with a cluster of stars.” The poem describes the speaker’s great-grandfather responding to a job ad for “painting / the interiors of first class cars,” selling his old horse and, with the sale money, purchasing “tubes of lead white, Naples yellow, // French ultramarine, and a fifth of Silver Leaf Whiskey.” The speaker wonders: “I think of your blood in my blood // and of how all endings are piteous the way they seem to verge / on other fire-lit worlds, kinder, impossibly close.” In this intimate portrayal of family labor (much better as a poem than as critical summary), I am reminded of genetic mirroring in birth family members, and how important it is to see oneself reflected in others—that it makes meaning of the speaker’s world, and both situates and propels the speaker forward into their own life. Poems that do this historical work attune themselves to political and class realities; they make more truth in the world, instead of less. There is such beauty in what they document.

The poet Philip Larkin wrote of his own time, “It becomes still more difficult to find / Words at once true and kind, / Or not untrue and not unkind.” A poet who attends to words “not untrue and not unkind,” always makes me sit up and take note, as a reader. Joined with the beautiful craft of line and subject in My Bright Last Country, Jane Craven is a poet to seek out this year.